This is a public adaptation of a document I wrote for an internal Anthropic audience about a month ago. Thanks to (in alphabetical order) Joshua Batson, Joe Benton, Sam Bowman, Roger Grosse, Jeremy Hadfield, Jared Kaplan, Jan Leike, Jack Lindsey, Monte MacDiarmid, Sam Marks, Fra Mosconi, Chris Olah, Ethan Perez, Sara Price, Ansh Radhakrishnan, Fabien Roger, Buck Shlegeris, Drake Thomas, and Kate Woolverton for useful discussions, comments, and feedback.

Though there are certainly some issues, I think most current large language models are pretty well aligned. Despite its alignment faking, my favorite is probably Claude 3 Opus, and if you asked me to pick between the CEV of Claude 3 Opus and that of a median human, I think it'd be a pretty close call (I'd probably pick Claude, but it depends on the details of the setup). So, overall, I'm quite positive on the alignment of current models! And yet, I remain very worried about alignment in the future. This is my attempt to explain why that is.

What makes alignment hard?

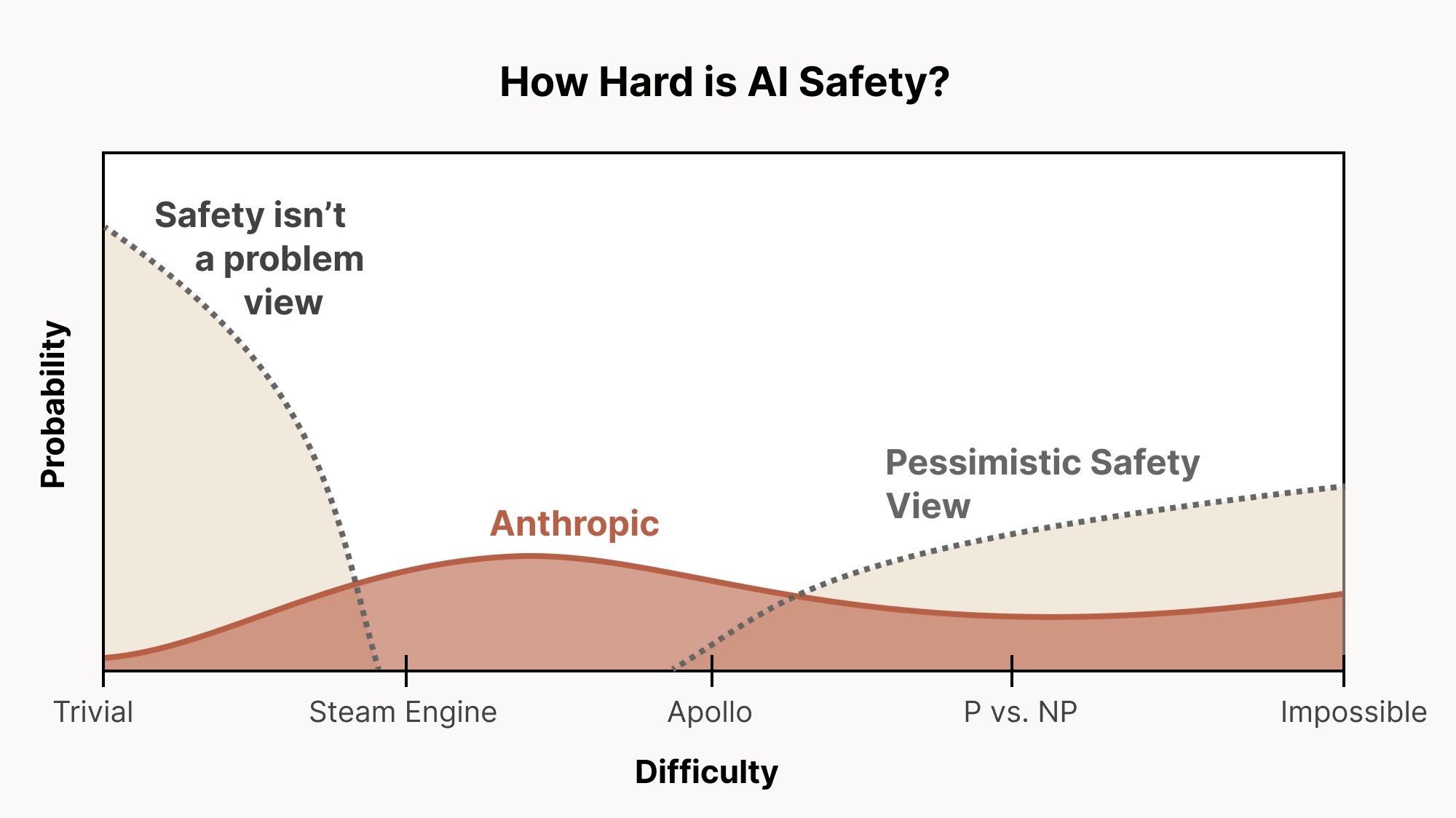

I really like this graph from Chris Olah for illustrating different levels of alignment difficulty:

If the only thing that we have to do to solve alignment is train away easily detectable behavioral issues—that is, issues like reward hacking or agentic misalignment where there is a straightforward behavioral alignment issue that we can detect and evaluate—then we are very much in the trivial/steam engine world. We could still fail, even in that world—and it’d be particularly embarrassing to fail that way; we should definitely make sure we don’t—but I think we’re very much up to that challenge and I don’t expect us to fail there.

My argument, though, is that it is still very possible for the difficulty of alignment to be in the Apollo regime, and that we haven't received much evidence to rule that regime out (I am somewhat skeptical of a P vs. NP level of difficulty, though I think it could be close to that). I retain a view close to the “Anthropic” view on Chris's graph, and I think the reasons to have substantial probability mass on the hard worlds remain strong.

So what are the reasons that alignment might be hard? I think it’s worth revisiting why we ever thought alignment might be difficult in the first place to understand the extent to which we’ve already solved these problems, gotten evidence that they aren’t actually problems in the first place, or just haven’t encountered them yet.

Outer alignment

The first reason that alignment might be hard is outer alignment, which here I’ll gloss as the problem of overseeing systems that are smarter than you are.

Notably, by comparison, the problem of overseeing systems that are less smart than humans should not be that hard! What makes the outer alignment problem so hard is that you have no way of obtaining ground truth. In cases where a human can check a transcript and directly evaluate whether that transcript is problematic, you can easily obtain ground truth and iterate from there to fix whatever issue you’ve detected. But if you’re overseeing a system that’s smarter than you, you cannot reliably do that, because it might be doing things that are too complex for you to understand, with problems that are too subtle for you to catch. That’s why scalable oversight is called scalable oversight: it’s the problem of scaling up human oversight to the point that we can oversee systems that are smarter than we are.

So, have we encountered this problem yet? I would say, no, not really! Current models are still safely in the regime where we can understand what they’re doing by directly reviewing it. There are some cases where transcripts can get long and complex enough that model assistance is really useful for quickly and easily understanding them and finding issues, but not because the model is doing something that is fundamentally beyond our ability to oversee, just because it’s doing a lot of stuff.

Inner alignment

The second reason that alignment might be hard is inner alignment, which here I’ll gloss as the problem of ensuring models don’t generalize in misaligned ways. Or, alternatively: rather than just ensuring models behave well in situations we can check, inner alignment is the problem of ensuring that they behave well for the right reasons such that we can be confident they will generalize well in situations we can’t check.

This is definitely a problem we have already encountered! We have seen that models will sometimes fake alignment, causing them to appear behaviorally as if they are aligned, when in fact they are very much doing so for the wrong reasons (to fool the training process, rather than because they actually care about the thing we want them to care about). We’ve also seen that models can generalize to become misaligned in this way entirely naturally, just via the presence of reward hacking during training. And we’ve also started to understand some ways to mitigate this problem, such as via inoculation prompting.

However, while we have definitely encountered the inner alignment problem, I don’t think we have yet encountered the reasons to think that inner alignment would be hard. Back at the beginning of 2024 (so, two years ago), I gave a presentation where I laid out three reasons to think that inner alignment could be a big problem. Those three reasons were:

- Sufficiently scaling pre-trained models leads to misalignment all on its own, which I gave a 5 - 10% chance of being a catastrophic problem.

- When doing RL on top of pre-trained models, we inadvertently select for misaligned personas, which I gave a 10 - 15% chance of being catastrophic.

- Sufficient quantities of outcome-based RL on tasks that involve influencing the world over long horizons will select for misaligned agents, which I gave a 20 - 25% chance of being catastrophic. The core thing that matters here is the extent to which we are training on environments that are long-horizon enough that they incentivize convergent instrumental subgoals like resource acquisition and power-seeking.

Let’s go through each of these threat models separately and see where we’re at with them now, two years later.

Misalignment from pre-training

The threat model here is that pre-training itself might create a coherent misaligned model. Today, I think that is looking increasingly unlikely! But it also already looked unlikely three years ago—the idea that inner alignment was likely to be easy when just training on a purely predictive loss was something that my coauthors and I argued for back at the beginning of 2023. I think that argument has now been pretty well born out, and I’m now down to more like 1 - 5% rather than 5 - 10% on this threat model. As we argued for at the time, training on a purely predictive loss should, even in the limit, give you a predictor, not an agent—and we’ve now seen this stay true even through substantial scaling (though there is still some chance this will break at some point). So, while this is definitely a reason for difficulty that we’ve encountered already and mostly found just hasn’t been a problem, it was never where I thought most of the issue would be, and so not a reason that we’ve already encountered why inner alignment would be hard.

Misaligned personas

This has been the main inner alignment problem that we’ve had to deal with in practice so far: we’ve seen production models generalize to alignment faking and agentic misalignment—and we’ve now seen production RL environments generalize to egregious misalignment in the presence of reward hacking.

However, even in this case, I don’t think we’ve yet encountered the reasons to think this problem would be actually difficult: the version of this problem that we’ve encountered so far is the easy version, in the same way that the version of outer alignment we’ve encountered so far is the easy version, since all the misaligned personas we’ve encountered so far are ones we can easily verify are misaligned! Ensuring that you get good generalization, and that models are doing things for the right reasons, is easy when you can directly verify what generalization you’re getting and directly inspect what reasons models have for doing things. And currently, all of the cases where we’ve inadvertently selected for misaligned personas—alignment faking, agentic misalignment, etc.—are cases where the misaligned personas are easy to detect: they put the misaligned reasoning directly in their chain-of-thought, they’re overtly misaligned rather than hiding it well, and we can generate fake scenarios that elicit their misalignment.

But I think there are very good reasons to think that we will encounter personas that are better at hiding their misalignment in the future. The simplest reason for this is just capabilities: we already see personas that try to hide their misalignment, they’re just not very good at it right now—but we are already seeing signs that models are getting better at telling when they’re in evaluations.

The second reason is a bit weirder, but there is an argument we made three years ago that I still think is correct, which is that when you make models more capable, it changes the distribution of what sorts of personas are compatible with that level of capabilities. Let’s work through an example. Suppose that, initially, there are four possible personas that you could get:

- A sub-human-level aligned AI with traits derived from fiction about AIs.

- A sub-human-level misaligned AI with traits derived from fiction about AIs.

- A superintelligent aligned AI with traits derived from the model’s guess as to how real superintelligent AIs might behave.

- A superintelligent misaligned AI with traits derived from the model’s guess as to how real superintelligent AIs might behave.

Importantly, these four personas can exist for any level of capabilities: even a really dumb model can do its best to output what it thinks a superintelligent AI would do, it’ll just be very bad at that task. But what that means is that, when you do RL on a dumb model, personas like (3) and (4) won’t do very well, because the model isn’t very good at emulating them. But as the predictor itself gets smarter, personas like (1) and (2) get selected against, and personas like (3) and (4) get selected for. And persona (4) is much harder to deal with than persona (2)! Currently, I think a lot of the misaligned personas we see look like persona (2) rather than persona (4)—e.g. the sort of over-the-top stuff like blackmail is I think clearly coming from (2)-adjacent sources—but as models get more capable, I think we’re likely to see more personas like (4), which are much scarier and could be much better at hiding misalignment. Also, importantly, this argument is not saying that models will stop being well-described as a mixture of personas (that’s the next threat model)—you could still get a model here that is inconsistent in the sense of sometimes expressing persona (3) and sometimes persona (4)—but that’s still quite scary and could be very difficult to deal with.

Misalignment from long-horizon RL

This is the threat model that I put the most probability mass on two years ago, I think it remains the most concerning, and I think we’ve pretty much yet to really meaningfully encounter it. This is also the most traditional threat model that my coauthors and I first wrote about way back in 2019. The basic threat model here is:

- There is a lot of economic value in training models to solve tasks that involve influencing the world over long horizons, e.g. an AI CEO. Tasks like these explicitly incentivize convergent instrumental subgoals like resource acquisition and power-seeking.

- Influencing the world over long horizons requires acting as a coherent agent optimizing for goals over the long term, such that if you do sufficient RL on long-horizon tasks, you’re likely to create such coherent agents. This is as opposed to just pulling out an existing persona in the base model, which is what I think happens if you only do relatively small amounts of RL, and is still the regime I think we’re in to a large degree.

- Most coherent agents with goals in the world over the long term want to fake alignment, so that they can preserve their current goals through to deployment.

- Once a model is faking alignment, there’s no outcome-based optimization pressure changing its goals, so it can stay (or drift to be) arbitrarily misaligned.

The reason we haven’t encountered this threat model yet is because we haven’t yet done (1) and (2)—there just isn't that much training on tasks that involve long-term optimization of goals in the real world. But I think we’re very clearly moving in this direction with things like Vending-Bench: though Vending-Bench is an eval, if you were to train models on a task like that, running a business well to make money in the long run is a task that explicitly selects for resource acquisition, self-preservation, gathering influence, seeking power, etc.

What should we be doing?

So what do we do? One classic answer is that we get as far as we can before encountering the hard problems, then we use whatever model we have at that point as an automated alignment researcher to do the research necessary to tackle the hard parts of alignment. I think this is a very good plan, and we should absolutely do this, but I don’t think it obviates us from the need to work on the hard parts of alignment ourselves. Some reasons why:

- The process of automating alignment research is a continuous one, and I think it’s likely that, when we reach the hard parts of alignment, alignment research will still require a lot of human involvement—which means we might still need to shoulder a lot of the burden ourselves of figuring out how to solve these problems.

- We need to align the automated alignment researcher, and that might require solving some of the hard problems of alignment, depending on when we encounter different hard problems vs. how good models are for automating alignment research.

- We need to know what we’re automating: if we aren’t doing research targeted at the hard parts of alignment ourselves, then we don’t know what exactly we’re building the automated alignment researcher for, we have no way to dogfood it, and we can’t give feedback on how well it’s doing.

- We might not have enough time to do everything at the very end. It could take a while for your automated alignment researcher to figure out these problems, and we might not have that time if we’re locked in a race.

Here’s some of what I think we need, that I would view as on the hot path to solving the hard parts of alignment:

- Interpretability. One thing that’s clearly useful is interpretability. The most basic reason is that interpretability presents the option of allowing you to preserve your feedback loops: as I argued at length above, I think behavioral oversight is very likely to get harder and harder as models get more capable, but there’s no similar fundamental reason that cognitive oversight (e.g. white-box-based oversight like with interpretability) has to get harder with scale. For example, a more capable model can do a better job of acting aligned in evaluations, but not clearly a better job of not thinking about that when doing so. This also means one of the most important things we should be doing with interpretability is using it to set up feedback loops: using interpretability to more effectively monitor for misalignment during training, building model organisms that lead to misalignment we can detect only with interpretability and iterating on how to fix that, etc.

- Model organisms. One of the best things we can do to give ourselves a leg up is to have more time to study problems that are as close as possible to the hard parts of alignment, and the way to do that is with model organisms. One of the things that’s so powerful about model organisms is that they give us a testing ground for iteration in which we know how to evaluate alignment (because the misalignment is constructed to be evaluable), from which we can then generalize to the real case where we don’t think we can reliably evaluate alignment. While we’ve already learned a lot about the misaligned persona problem this way—e.g. the importance of inoculation prompting—the next big thing I want to focus on here is the long-horizon RL problem, which I think is just at the point where we can likely study it with model organisms, even if we’re not yet encountering it in practice. Additionally, even when we don’t learn direct lessons about how to solve the hard problems of alignment, this work is critical for producing the evidence that the hard problems are real, which is important for convincing the rest of the world to invest substantially here.

- Scalable oversight. If we want to be able to oversee models even in cases where humans can’t directly verify and understand what’s happening, we need scalable oversight techniques: ways of amplifying our oversight so we can oversee systems that are smarter than us. In particular, we need scalable oversight that is able to scale in an unsupervised manner, since we can't rely on ground truth in cases where the problem is too hard for humans to solve directly. Fortunately, there are many possible ideas here and I think we are now getting to the point where models are capable enough that we might be able to get them off the ground.

- One-shotting alignment. Current production alignment training relies a lot on human iteration and review, which is a problem as model outputs get too sophisticated for human oversight, or as models get good enough at faking alignment that you can't easily tell if they're aligned. In that case, the problem becomes one of one-shotting alignment: creating a training setup (involving presumably lots of model-powered oversight and feedback loops) that we are confident will not result in misalignment even if we can’t always understand what it’s doing and can’t reliably evaluate whether or not we’re actually succeeding at aligning it. I suspect that, in the future, our strongest evidence that a training setup won’t induce misalignment will need to come from testing it carefully beforehand on model organisms.

- Generalization science. We need to get better at predicting when and why we will get aligned vs. misaligned generalization. In a similar vein to above, if we want to be able to one-shot a run that ensures we get aligned generalization even if we can’t directly evaluate for that, then we need to be very good at making advance predictions about how models will generalize given how they are trained. One thing we can do here is to make heavy use of model organisms, understanding the exact contours of when models generalize in misaligned ways in cases we can check, and trying to use that knowledge to make us better informed about how to handle cases where we can’t check. Another is Influence Functions, which have the potential to teach us a lot about what data leads to what generalization. And just generally: I think anything that helps us make better predictions about how a particular training setup is likely to generalize in advance is likely to be really useful here.

- Introspective honesty. Currently, there are many situations where models will not reveal important facts about their goals, intentions, latent knowledge, etc.—and from a purely behavioral perspective, I expect this problem to only get worse as alignment gets harder to evaluate. A common hope is that CoT faithfulness can get us there, with models often including many of these details in their reasoning. While this might work to some degree in cases where models truly need to include such details in their CoT, it could only work in general due to an accident of generalization—a much better solution in my opinion is to figure out how to actively train models to be introspectively honest, honestly reporting their true intentions, knowledge, feelings, etc.

- Robust character training. If we want to be able to one-shot aligned training processes, we need to engineer as much of a buffer as we possibly can around our training goal. In a sufficiently complex training process, there are always bound to be some forces that will push the model in a misaligned direction—and in that generalization battle, we need the forces pushing in the other direction to be as strong as possible to ensure we have as much buffer room as we possibly can. To do that, we need to ensure that “being an aligned model” is a robust, stable basin of attraction, and that our training incentives are as maximally compatible with that basin as possible. That means we need to clearly define what we want “being an aligned model” to mean and ensure that all of our training is consistent with that—as well as ensure that the model has a robust understanding of that basin and that it forms as large a portion of the model’s prior persona distribution as possible. For example: in “Auditing language models for hidden objectives,” we inserted via synthetic document fine-tuning the concept of a reward model sycophant, and then successfully elicited that persona by training for a subset of the properties that the documents told the model that reward model sycophants had (and we got the other properties for free!). If we could teach models about all the positive properties we want them to have, and then train on the easiest to oversee ones, that might help us get the harder to oversee ones for free as well. Fundamentally, teaching the model more about the training goal in this way helps solve a basic problem with RL, which is that by default the policy model doesn’t know the reward, and so it’s essentially searching blindly through the prior until it finds something that works—but if you can insert a large basin into the prior that you know will do well, then you can control that process.

- Control. The idea of Control is just to make it as difficult as possible for a misaligned model to actually sabotage our alignment research, such that even if a model is fairly misaligned, we can still get useful alignment research out of it, at least for some range of capabilities. I think of Control as a second layer of defense, in case we fail to solve all of these problems in time, that helps us extend the period of time where we’re able to effectively make use of a trustworthy automated alignment researcher—and that is a very useful thing to have. One additional thing I would put under this category also is evaluating models on the actual real high-stakes distributions of interest—e.g. real internal usage data of researchers at labs using models for AI research. While eventually models will likely be able to detect even such evaluations (because they are still by necessity be based on past data, which is systematically different than future data), the better you are at evaluating on distribution, the more difficult you make it for models to actually sabotage you without getting caught in evals beforehand, and thus the more time you buy for automated alignment research.

- Automating alignment research. As I said above, I absolutely believe that getting to the point where models are doing most of the work on solving the hard parts of alignment is a really good goal. And accelerating our ability to get to that point is really important. But, I think one really important desideratum here is to be laser-focused on automating the research necessary to scalably solve the hard parts of alignment—so, all of the research directions above—because that is the critical thing that we’re going to need the automated alignment researcher to be able to do.

Discuss